Talented designer contributed to the beauty of Padua

Architect Andrea Moroni, who designed many stunning buildings in Padua and the Veneto region, died on 28 April 1560, 536 years ago

today, in Padua.

Padua's Basilica di Santa Giustina is one of

Andrea Moroni's best known works

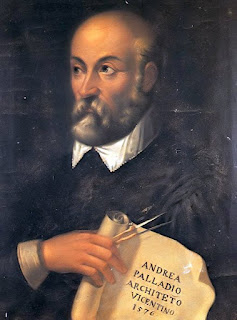

Moroni was the architect of some acclaimed Renaissance buildings but

has tended to be overlooked by architectural historians because his career

coincided with that of Andrea Palladio.

Moroni, who spent most of his working life in Padua, made

a name for himself with the Benedictine Order and obtained commissions for two

Benedictine churches in Padua, Santa Maria di Praglia and the more famous Santa

Giustina.

His contract with Santa Giustina was renewed every ten

years until his death and he settled down to live in Padua.

He was commissioned by the Venetian Government to

build the Palazzo del Podestà, which is now known as Palazzo

Moroni in Via VIII Febbraio, and is currently the seat of Padua city council.

It is considered one of the most significant Renaissance buildings in the

entire Veneto region.

Moroni was also involved in the construction of the

Orto Botanico, Padua’s famous botanical gardens, where medicinal plants were

grown, and he designed some of the university buildings.

It is known that he supervised the construction of Palazzo

del Bo, the main university building in the city, but there

is some controversy over who designed the palace’s beautiful internal

courtyard. Famous names such as Sansovino and Palladio have been suggested,

rather than Moroni, contributing to his talent tending to be overlooked over

the centuries. .jpg)

The Orto Botanico, the world's first botanical

gardens, was designed by Moroni

The Loggia of Palazzo Capitaniato and the 16th century Palazzetto are also attributed to him.

Born into a family of stonecutters, Moroni was the

cousin and contemporary of Giovan Battista Moroni, the brilliant painter. They

were both born in Albino, a comune to the north east of Bergamo in Lombardy. The

architect has works attributed to him in Brescia, another city in Lombardy

about 50 kilometres to the south east of Bergamo. He is known to have been in

the city between 1527 and 1532, where he built a choir for the monastery of

Santa Giulia.

He probably also designed the building in which the

nuns could attend mass in the monastery of Santa Giulia and worked on the

church of San Faustino before moving to live and work in Padua.

.JPG)