Risorgimento novel now seen as an overlooked classic

The writer Ippolito Nievo, a passionate supporter of the move to unify

Italy in the 19th century, was born on this day in 1831 in Padua.

Nievo, whose posthumously published Confessions of an Italian is now

considered the most important novel about the Risorgimento in Italian

literature, drew inspiration from his participation in Giuseppe Garibaldi’s

Spedizione dei Mille - the Expedition of the Thousand.

|

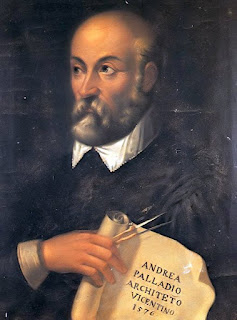

Ippolito Nievo fought for a united Italy

|

Nievo was born into comfortable circumstances. His father was a

prominent lawyer and magistrate in Padua and his mother the daughter of a

Friulian countess. Their home in Padua was the Palazzo Mocenigo Querini,

a 16th century house overlooking Via Sant’Eufemia, close to the city centre.They also had use of his mother’s ancestral home, a castle in Colloredo

di Montalbano, a hamlet just outside the city of Udine in Friuli-Venezia

Giulia, and of the Palazzo Nievo in Mantua.

From 1832 to 1837, when Nievo was a small child, they lived in a house

adjoining the Palazzo della Giustizia in Soave, about 60km (37 miles) from

Padua, where his father was posted as a judge.

By the late 1840s, Nievo was becoming increasingly fascinated by the

writings of Carlo Cattaneo and Giuseppe Mazzini, two of the central

philosophical drivers of the Risorgimento.

He is thought to have taken part in a failed uprising in Mantua in 1848,

a year marked by a series of insurrections inspired by Italian nationalists seeking

to overthrow the Austian grip on the north of the country.

He had been inspired by conversations with his maternal grandfather,

Carlo Marin, who had been a prominent official of the Venetian Republic when it

fell to the Austrians in 1797.

Nievo refused to follow his father into the law as he felt it would

imply submission to the Austrian government and instead pursued a career in

journalism.

In the 1850s he retreated to Colloredo di Montalbano, where he wrote a

number of novels set in the Friulian countryside, as well as volumes of short

stories and poetry.

|

Most important novel

about the Risorgimento |

He began writing his major work, Confessions of an Italian, at some

point in the mid-1850s. The central character is an 83-year-old man, Carlo

Altoviti - thought to be based at least loosely on Carlo Marin - who has

decided to write down the history of his long life, from an unhappy childhood

to romantic entanglements during the siege of Genoa, and fighting in the cause

of revolution in Naples.

Carlo’s twin passions are the dream of a unified, free Italy and his

undying love for Pisana, the woman with whom he is obsessed. With characters

ranging from drunken smugglers to saintly nuns and scheming priests, as well as

real figures such as Napoleon and Lord Byron, it is an epic novel that tells the

remarkable and inseparable stories of one man's life and the history of Italy's

unification.

Nievo’s political activity intensified in the late 1850s, when he joined

Garibaldi’s Cacciatori delle Alpi, a brigade of volunteers fighting to liberate

Lombardy, and then participated in the Expedition of the Thousand, given the

number 690 in the list of 1,000 patriots.

Nievo embarked from Genoa on 5 May, 1860 setting sail for Sicily. After

distinguishing himself in the battle of Calatafimi and in Palermo, he was

promoted to colonel and took on administrative assignments, at the same time

keeping diaries that served as a chronicle of events.

It was in this role that he was tasked with bringing back from Sicily

all the administrative documents and receipts from the expedition’s expenses.

He boarded the steamship Ercole along with other members of the military

administration to travel from Palermo to Naples, but during the night between

March 4 and 5, 1861, the steamship ran into difficulties off the coast of Sorrento,

almost within view of the Bay of Naples, and sank. There were no

survivors.

Nievo’s life is commemorated in a number of locations, including

Colloredo di Montalbano and Fossalta di Portogruaro, in the Veneto, where the

Castello di Fratta, the scene of Carlo Altoviti’s unhappy childhood, was

thought to be located.

Colloredo di Monte Albano - known locally as Colloredo di Montalbano -

is a small village in Friuli-Venezia Giulia situated about 14km (9 miles)

northwest of Udine. In the 11th century, it was a fief of the Viscounts

of Mels, who had received it from the Counts of Tyrol. In 1420, together with

all of Friuli, the hamlet was acquired by the Republic of Venice. The hamlet was

severely damaged by the Friuli earthquake in 1976, yet the family castle remains

intact.

Nievo’s legacy is preserved in his novel, in which the central character

and narrator shares Nievo’s passions. Nievo completed the work in 1858 but it

was not until 1867, six years after his death, that it was published.

When Nievo’s supporters first found a publisher the book was titled

Confessioni di un ottuagenario (Confessions of an octogenarian), because

Nievo’s intended title was still deemed politically sensitive. It was changed

later to reflect the author’s wishes.

Nievo died for the cause he believed in passionately, at the age of

just 29.

Home

.jpg)

.JPG)